Creating Young Universes with Marc Standing

Painter

Hong Kong, China

June/July 2017

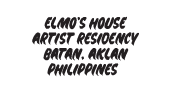

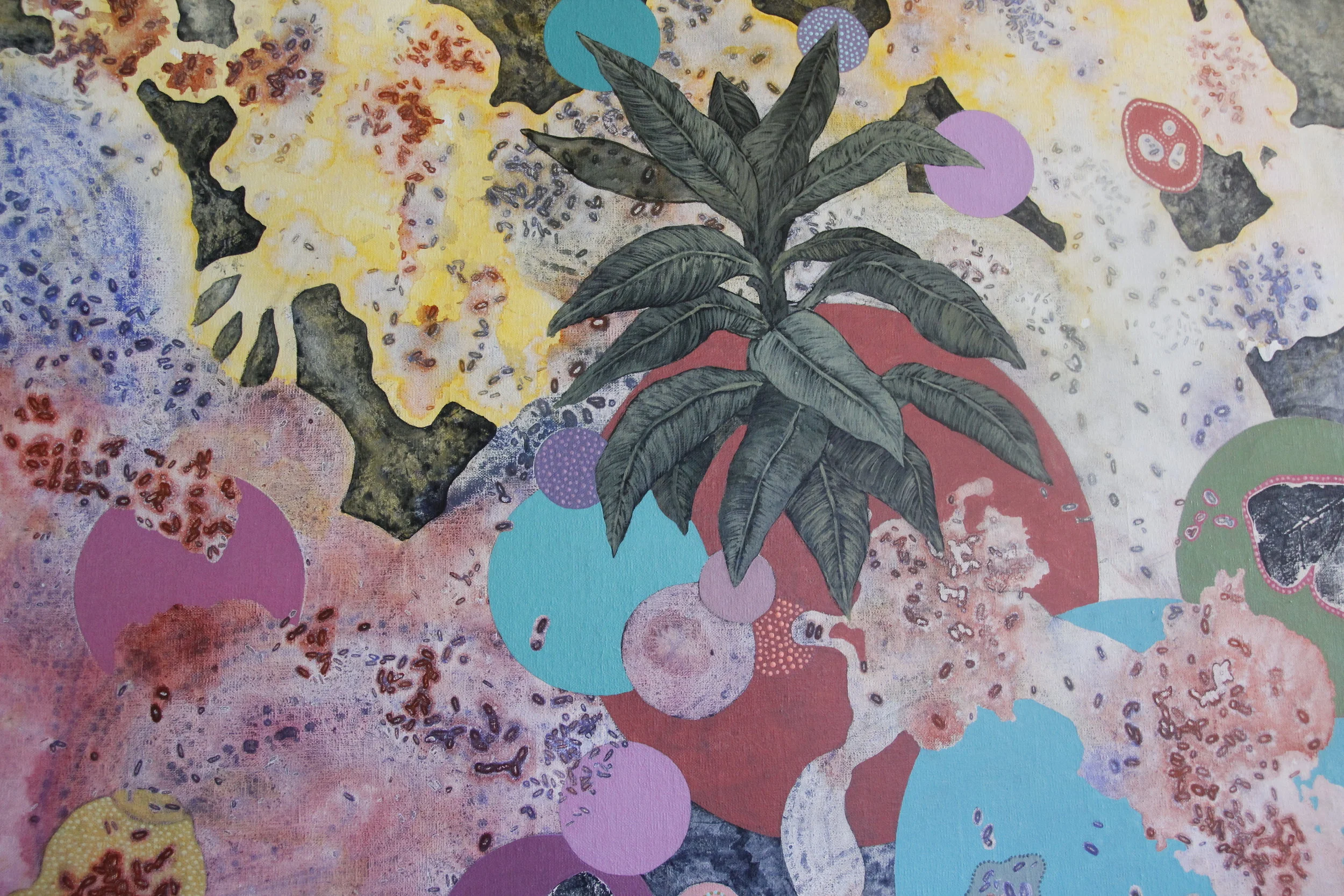

It is difficult to say where exactly Marc Standing comes from or where he calls home. He was born in Zimbabwe, and has spent considerable time in Australia, UK and Hong Kong. In between, he has travelled all over the world in places whose names are hard to recall. Perhaps for Marc, it was never important to establish home through geography. From observation, Marc finds contentment in a small square footage — seated on a cushioned chair in front of a canvas surrounded by paints. From this basic environment, he creates young universes with floating imagery of botanical inspiration and cellular shapes. True of all the paintings he created in Batan, his imagery floats in perpetual motion. They move in voids of fantastical colours of acidic greens and turquoise, on cusp of colliding into genesis.

Initially, Marc proposed a project based on the region's elaborate mythology and folklore that still penetrate modern life. However prior to arrival, an opportunity to exhibit in a group show in China soon after the residency, prompted a change in plans. Instead, the duration of his time at Elmo’s House was spent creating six large paintings for the show geared for the Chinese Art market. The influence of Batan was subtle but still palpable in the works produced. Grains of Milagrosa rice and Borabocay sand was used to create patterns on the canvas. Plucked foliage from neighbouring gardens provided negative impressions for his compositions. Marc’s colour palette reflected the personalized aesthetic of the houses and buildings that interject the rural landscape visible from the studio. The bold pink and purple hues of his paintings references the same extraordinary colours in the sky, a nightly show before darkness descends.

The belief of communicating with ancestors in the spirit world or being able to see things that are unseen, can help us explain the world around us. It can definitely hold up a mirror to our humanity.

Marc started painting when he was 16 years old. He has a Bachelor in Fine Arts from the University of Cape Town and is currently represented by galleries in Sydney, Melbourne, Hong Kong and Shanghai. Marc's work is known for the complex layering of otherworldly textures and images with a motivation to create art as a means of revealing a “hidden knowledge”. It inspires in the viewer an ethical and harmonious way of life. It triggers a search for identity that reminds one's position within humankind’s age-old search for enlightenment. He brought a spiritual curiousness to the Residency that was fuelled by Batan's religious rites, traditions and iconography.

Growing up in Zimbabwe, your mother helped seek out a mentor for you when you were 16 years old. She was key in nurturing your talent. Can you describe that time in your life?

I was born in Zimbabwe and grew up there until my late twenties. Since I was young I was always into drawing and painting and knew that this was the one thing I had a real passion for. I went to a school that didn’t provide art classes in their curriculum, so I went to art classes at another college. Helen Lieros ran these classes and also had one of the few contemporary galleries, Gallery Delta, in Harare. Helen became one of my first mentors. I was one of the youngest students she took on. Before accepting me she asked me to come in and do a three hour class. I could paint whatever I wanted. I made a painting of a crow, which I superimposed in different positions. She loved it and took me on. Helen was a fiery and passionate teacher with very liberal teaching methods. It was up to you to decide what you wanted to paint, so there were no constrictions to the classes. It was the most inspiring way to learn and express myself. Years later while I was completing my arts degree I would return home and still go paint with her. By then she had left the college and conducting classes at her gallery every Saturday morning. My very first exhibition after graduate school was a two man show at her gallery. Helen Lieros' support has partly got me to where I am today.

What was her studio like?

The studio was filled with all sorts of objects, from taxidermy birds, fabrics, plants, shells and pods, many objects gathered from the natural world. There was even a match box which had a tiny dead bird in it. Under her tutelage, we were encouraged to paint or draw exactly what we wanted. It was a method that prepared me for art school years later. At the end of each class, Helen would crit our work. To this day much of my inspiration is drawn from the same sort of objects found in her studio… a curious cabinet of sorts. I still gather and collect such objects.

Batan has a myriad of religious symbols and shrines in and around the homes and buildings. You are often found taking a photograph. Religious iconography is something that has always greatly interested you. Is there a difference between religion and spirituality in the Philippines compared to other countries?

I am more of a spiritualist and not religious at all. However, I love religious iconography. It holds a certain power and can be gruesome, ornamental and kitsch all in one. Having lived in Africa, I was always intrigued by African religion. The belief of communicating with ancestors in the spirit world or being able to see things that are unseen, can help us explain the world around us. It can definitely hold up a mirror to our humanity. I also spent time in Mexico during the Day of the Dead and it was incredible to see this celebration of life and death merging into one. What fascinated me about the Philippines was this amalgamation of folklore and heightened superstition with a very strong sense of Catholicism. One would think they would be worlds apart but somehow they are both so entwined with each other.

Your past body of work depict mythical worlds inhabited by transcendental beings and sacred artifacts and yet are grounded in the familiar patterns of nature. Can you share with us how being in Batan, a small fishing village, affected your investigations?

Where ever I go I am always interested in the belief systems of the communities I visit. The spiritualist in me believes that there are things out there we cannot see, and I am intrigued by the idea of magic and superstition. I believe artists are shamans and a lot what we create is magic. Being in Batan, a small rural village was fascinating as it was a very real place in its depiction of how authentic Filipino people live. Every day the church bells would ring, yet under this cover of Catholicism, there was a parallel belief system of spirits and magic. Once night fell and the evening sounds took over, the town became dead quiet. It was dark, still, shadow-filled, street dog patrolled and bat populated. One can understand how under these pretenses another world could come into play.

Your intended project changed prior to arriving at the residency. An opportunity to be part of a group exhibition in Shanghai meant spending the two months at Elmo’s House completing six large paintings for the show. Would the paintings you produced at Elmo’s House be any different if you painted them anywhere else?

It did unfortunately, and I do hope to return so I can actually forge ahead with my intended proposal and after having experienced the country there are even more ideas I would want to explore. There is no way the works I produced at Elmo’s would have turned out the way they did if I had not been there. The light and colours around me heavily influenced much of the work and the paintings took on a much more gestural form. I don’t think this would have happened if I had been elsewhere.

Can you describe some of the symbols and shrines you’ve encountered here in the Philippines? What did you think of the gigantic Jesus statue just outside Roxas City?

The gigantic Jesus was amazing to see. It took religious iconography to another level! One of my favorite shrines I saw was on a tiny island near Cebu. There was a very small church and inside was a statue of Jesus and the Virgin Mary. Both were quite weathered from the salt. And because the statues were right by the ocean, both were covered in shells. Those were truly stunning objects that had a function as well. They were a reminder of the power of the ocean, of weather patterns and typhoons, and how strong natural forces can be. It reveals how the environment can affect our daily existence. In some instances it can mean life and death.

What is it about the icons in Batan that pique your interest?

I have never seen so much religious figurines inside these constructed semi oval stone coverings before. The amount of small churches everywhere you went was also quite unbelievable. It was an eye opener to see how strong Catholicism is embedded into the nation’s psyche. I also think that because many of the icons and shrines were exposed to more weathered conditions they had a more antiquated battered feel about them.

What fascinated me about the Philippines was this amalgamation of folklore and heightened superstition with a very strong sense of Catholicism. One would think they would be worlds apart but somehow they are both so entwined with each other

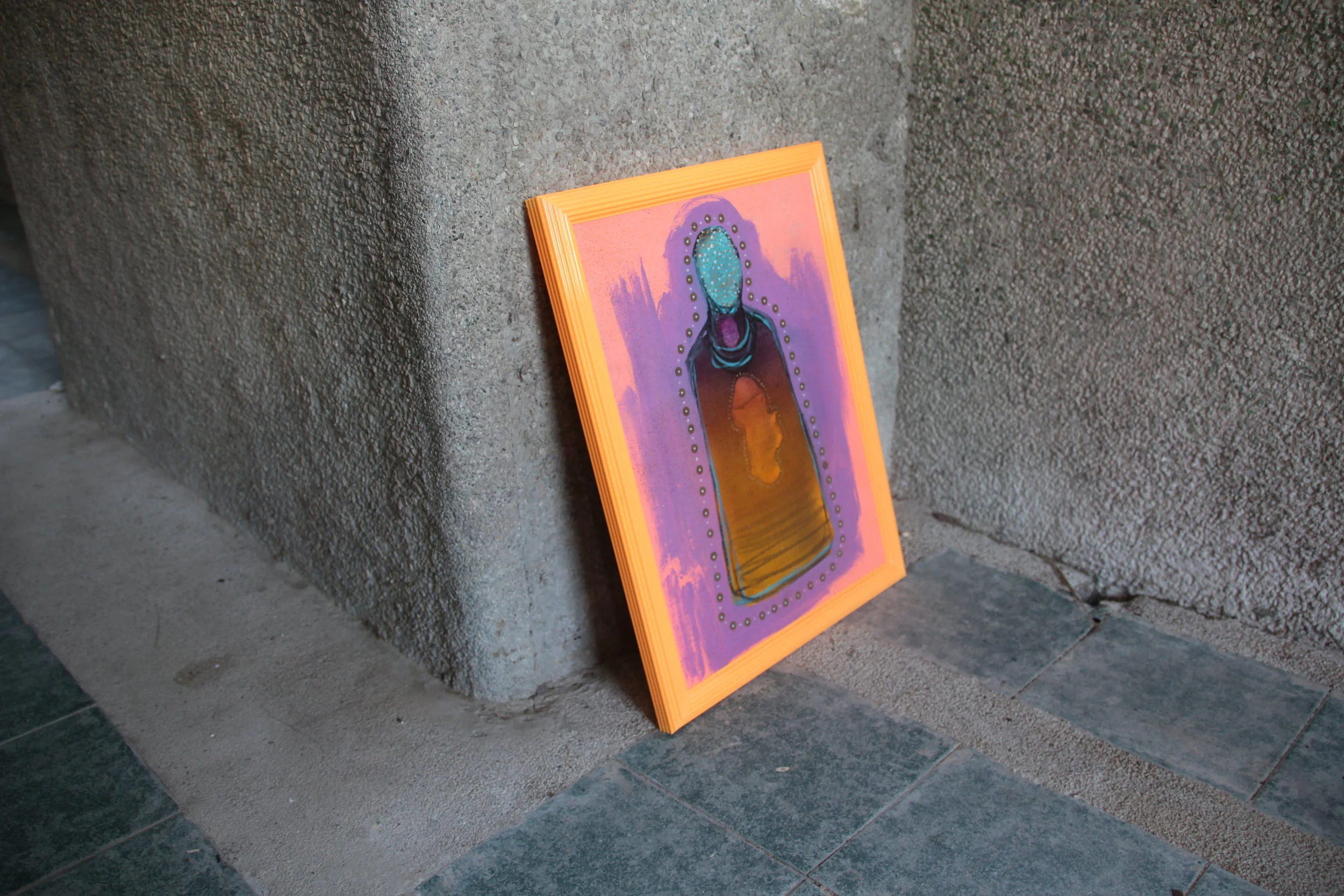

The Altar

In between paintings, you created a permanent installation at Elmo’s House. Can you explain your motivations and inspiration behind the work?

I loved creating this piece. It is something I have always wanted to do and to leave a permanent mark at the residency was a privilege. My inspiration was obviously derived from all the religious iconography around me and my interests in assemblage and objects. I was also very aware of ensuring I kept cultural sensitivity in tact. I used shades of blue for the wall, inspired from the colour of the Virgin Mary. I left circles of the concrete wall showing through as I wanted to incorporate the actual space and leave evidence of it. The holes functioned as portholes into other worlds and realities. I produced a painting as the main focus point of the alter piece. The figure in this work was my own iconic relic, partly influenced from my African heritage. I assembled separate objects made from rubber fishing bouys, beads, and plastic flowers, which were fixed on the wall. I also incorporated living orchids, as I wanted a relationship between something living and the constructed artificial elements. Beads and rubber bands hung from each side of the wall and small-mirrored glass shards were randomly glued amongst all this. Finally, candles where placed on the ledge in true altar form keeping in mind how the burnt wax would run down the wall.

I assembled separate objects made from rubber fishing bouys, beads, and plastic flowers, which were fixed on the wall. I also incorporated living orchids, as I wanted a relationship between something living and the constructed artificial elements

I do think that solitude does affect the narrative of the work in a way that one begins to almost go into a meditative trance like state. One’s own unconsciousness and psyche begins to take shape in a visual medium that is quite magical.

Can you share with us your daily routine at Elmo’s House?

My daily routine stayed much the same. Mornings were early starts and I would usually be painting by 8:30/9AM. 12 noon was lunch. I'd be back to work all afternoon, broken up by dinner at 7, where all the Residents would eat together. Most evenings I was back in the studio right after until 10/11PM. However, there were days broken up by going to the beach and visiting the surrounding areas.

You had the studio all to yourself during your final month in Elmo’s House. Some of those days went late into the night. Dealing with work that explores unseen realms, mythology and spirituality. Does solitude or the night affect the narrative of your paintings?

I did and it was quite strange at first being up there on my own. I don’t usually work at night only because I prefer to use natural light when I paint. However, due to my deadline, night hours gave me the much needed time necessary to complete the work. I don’t think that it did really affect the psychology of the work, as much of it was already in process. I do think that solitude does affect the narrative of the work in a way that one begins to almost go into a meditative trance like state. One’s own unconsciousness and psyche begins to take shape in a visual medium that is quite magical.

Having stayed the longest at Elmo’s House, what have you gained during this time that would not have been possible in a shorter stay?

I spent two months at Elmo’s House and had a major break through with my painting in the last month I was there. This would not have happened in a shorter stay. Being able to immerse myself into the residency and to have the headspace and time was invaluable. What was also important was having, Residence Director, Kuh Del Rosario there to talk and discuss the progress of the work. Her eye and experience really helped me take on board what she had to say and push the work to another place. I think this is one of the most fantastic things about a residency, to go somewhere new, seep in the surroundings, become inspired, and have other creative people around you. This all takes some time so two months was a great period to do this. Three would have been perfect!

Marc's time at the residency was fruitful, not only for Marc but for the residency as well. Marc's paintings evolved as he made discoveries about the town, culture and The Philippines in general. This growth was what the residency needed to gain a deeper understanding of how the residency can best serve as a mediator between artist and place. Every now and then, Marc's altar is lit as an offering to the nearest benevolent being, to establish this place, the artists that have come before, and the ones to come.

Learn more about Marc Standing

marcstanding.com

@marcstanding